lead

on drawing

I felt the itch of it creep in when he was a couple of months old. Quieter than a craving, but equally persistent. I wanted to push soft lead against clean paper, to try and capture the this little face, this stretching body, before it slipped through my fingertips.

I knew that if I grabbed the nearest biro and the back of an envelope it wouldn’t happen; too unceremonious, too scrappy, too much room for it to go wrong and expose my desires as foolish nonsense. Instead, I made a big fuss of getting the equipment in: pushed the baby around a paper shop and bought a wincingly expensive little sketchbook, selected three smart pencils yet to be sharpened. The cost alone would force me to act, to legitimise this indulgence.

At the time he was so small he began his nights sleeping on the floor of the kitchen, in the Moses basket we would move to wherever we were. And as the late spring nights stretched out and the dinner cooked I would try to draw him. It was terrifying, really, the thought of mangling something so perfect in an attempt to preserve it. So I stuck to just the parts of things: shadow of a Cupid’s Bow, arch of palest eyebrow. A few pages and I stopped. He started sleeping in his room. I put my noble ambitions in a box and carried on with domesticity. It made me notice things, like how the skin builds up beneath his hairline or where his veins trace through his forehead. It offered a few minutes to pause after a day of constant presence.

I stopped after a few days. The baby started sleeping in the bedroom, instead, and I felt vaguely preposterous doing it. I tucked the book alongside others, moved the pencils to a drawer. But on the second day in hospital, the really bad one - the one with no sleep and the vomit and the strange-coloured skin - my mum messaged: “Ask M to bring in your sketchbook - you could draw him as he sleeps xxx”. While C was in hospital, wired up and bleating, I would send lists of things we needed from the outside world. Nappies. Muslin. Crinkly toy newspaper. Pants. Pillow. M would arrive with them and they’d come in different forms from that I’d imagined: not the pillow I slept on but a cushion from the sofa. Not the sketchbook I’d bought but another, with good enough paper.

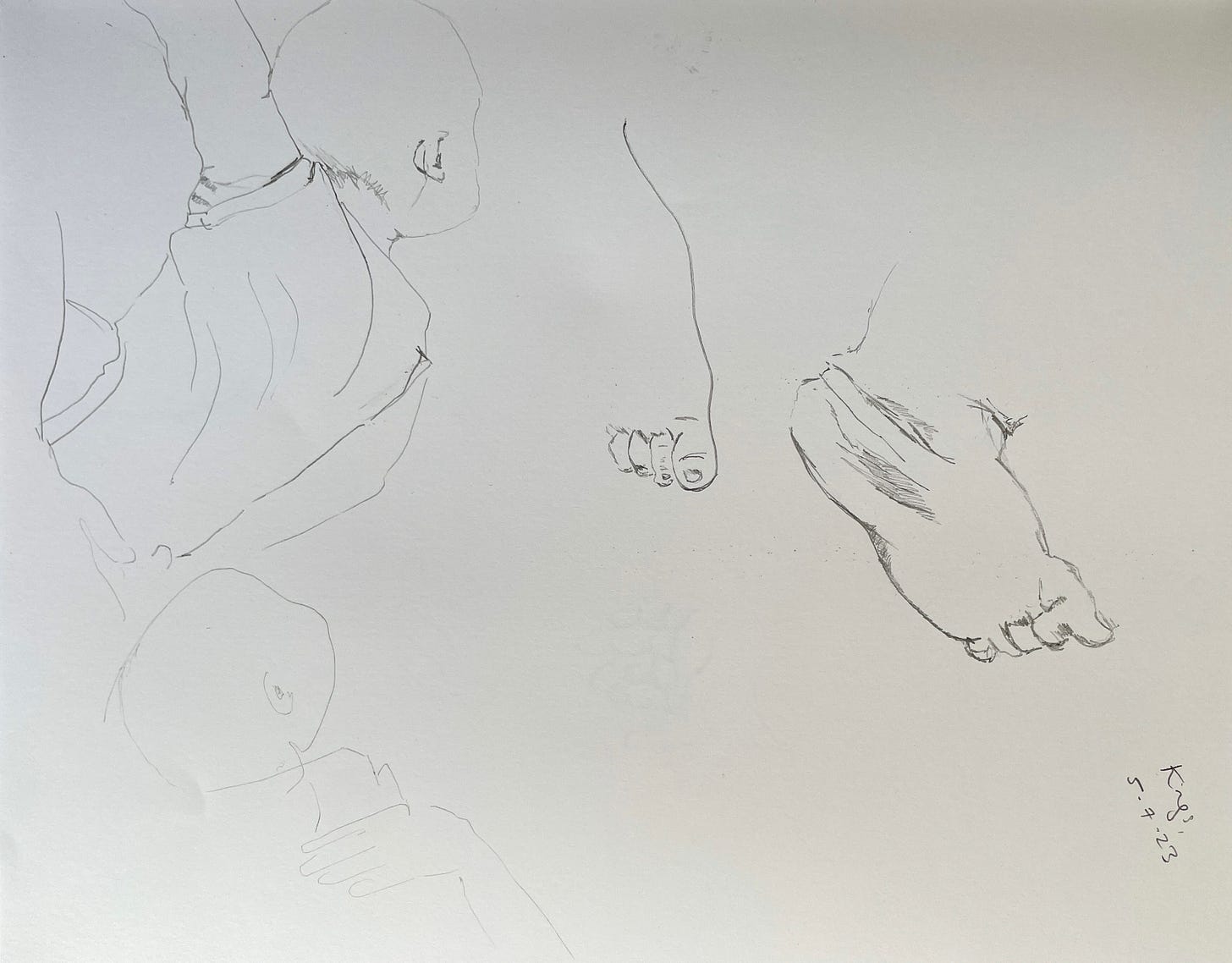

I started to draw the next morning. Feet, long and narrow, like mine. A curled hand with a tiny bloodstained plaster on its palm. A thumb hidden inside a fist. An ankle, a sole. A sleeping baby, arms unfolded against M’s chest. The ridges around a tiny vest. The crinkled hem of a nappy. The dark remnants of his newborn hair. It gave me something to focus on beyond the infection in his blood. It legitimised my futile gazing. This was a blank page, and now it has marks on. This is a point in time that made something, rather than just took things away.

It has been a long time since I carried a sketchbook with me. I began when I was a child and my parents wanted to keep me quiet in restaurants. I would draw things that came into my head - there was an era of wildly complex cruise ships - and also Spice Girls. I carried one when I was a teenager. I took a module in drawing at university. And then I stopped, got rusty and scared and put that creativity elsewhere. I still remember my preferred pencil (2B). There’s a handful of them inside an elastic band in a box where my old diaries live.

I suppose at some point I lost the fear of being disappointed in what I saw, of holding myself to an expectation of what things should look like. The critical voice in my head - so constantly present, about so many things - was quietened, perhaps by the bleeping of the machine that gently pushed drugs into his veins, or the raw surge of adrenaline coursing through mine. It didn’t matter if it wasn’t accurate, or the lines didn’t match up, or it didn’t look like him. I was doing this for the sake of doing it in a place where there’s so much and so little to do. There was great freedom in that.

Since we came home I have been thinking about drawing. I have drawn his pudgy little thigh, his fingers dimpling the flesh of it. I have flexed the muscle memory of turning a pencil on its side and dragging it gently across the surface of the paper to make a thick mark. I have played with cross-hatching and negative space. I’ve heard the words of my art teachers distantly return to my brain. Like handwriting, my style hasn’t changed. Scratchy, imprecise, never using a rubber. The lines made by my adolescent self are still there, like a thumbprint. I have kept the good habit of dating and noting the situation of the moment. Maybe one day this will be of interest.

Until then I will draw as he stretches out. The baby is growing. He kicks now, rolls over, laughs at sweet nothings and folds his fingers. He is only still when he sleeps, and that is my time. For short, precious minutes I can still and distill it. Boil it down into an exhale on a page.

The book will fill up with hands and feet and knees and chub and for a moment I will be able to remember what it was to hold it all in the palm of my hand.

How the blazes did I miss this the first time around? So glad I caught it this time, thank you for reposting these truly precious lines. And here's to feeling vaguely preposterous and doing it anyway. Xx

So glad to hear that the little one is feeling better. ❤️